eBook: Using Behavioral Science to Encourage Water Conservation

A Brief History of Social Influence Research

Perhaps one of the most well-known and widely applied areas of behavioral science centers on social influence and the related concept of social norms. Psychologists have understood for some time that people are profoundly influenced by those around them, often in ways that one might not expect.

One of the earliest experiments in social influence research revealed that people would consistently change their judgments about something as seemingly concrete as the length of a line in order to match the judgments of those around them, even when the group’s judgments were blatantly incorrect.

The Influence of Psychology and Social Factors on Water Conservation

Social and psychological aspects also have a significant impact on how consumers make decisions regarding resource usage.

This realization has led to a heightened interest in behavioral science, a multidisciplinary field that draws from psychology, sociology, public health, and behavioral economics to explain the complex mechanisms that shape human behavior.

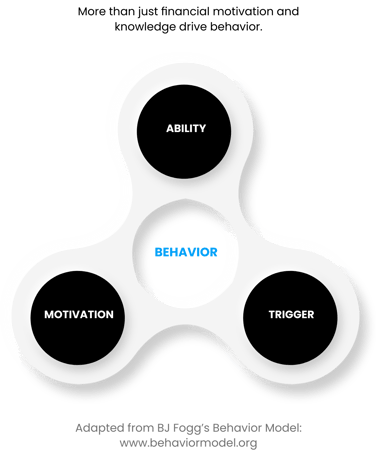

Over the past decade, utilities, governments, businesses, and nonprofits have come to realize that more than just financial considerations and information drive behavior. Social and psychological factors also play a significant role in shaping consumers’ decisions and behaviors around water use.

Stakeholders have consequently turned their focus to behavioral science, a multidisciplinary field that draws from psychology, sociology, public health, and behavioral economics to explain the complex mechanisms that shape human behavior. When used strategically, behavioral science holds the potential to generate measurable gains in water-use efficiency and drive up profits.

Some have speculated that our drive to conform to others’ behaviors and beliefs is rooted in the evolutionary need to affiliate and build social bonds with others. Other psychologists have speculated that following the lead of those around us can help us to maintain a positive self-image, which is a deep psychological need.

Another possible explanation is that mimicking the behavior of others provides a decision-making shortcut: if everyone else is doing something, it must be a sensible thing to do.

Leveraging Social Norms to Change Behavior

The power of social influence is undeniable, especially in terms of adhering to social norms. These norms are essentially beliefs about what others are doing, and what is considered acceptable or not.

Since social norms serve as a standard, people generally prefer to conform to them.

Ironically, people are often unaware of the extent to which social norms affect their behavior. In a particular experiment, the participants rated societal behavior as the least compelling reason for reducing energy use. However, the results of the study clearly indicated that social norms had a more significant impact on their actions than other factors did.

What is truly “normal” among their friends, peers, or neighbors can make them more likely to adjust their behavior to match that of those around them.

Social norms have also been successful in altering individuals’ environmental behavior. It’s also been known that people who received normative information about their neighbors’ recycling habits, as well as information about their own recycling habits, recycled significantly more than those who received information about how and why they should recycle.

Maximizing Efficacy of Norms

Though giving people information about social norms is a proven method for generating behavior change, social norms programs demand a sophisticated understanding of how a variety of psychological factors interact to produce meaningful behavior change.

When implementing social norms interventions, it's crucial to consider the coupling of descriptive norms, which illustrate what is typical in a group (the is), with injunctive norms, which illustrate what is socially acceptable in a group (the ought).

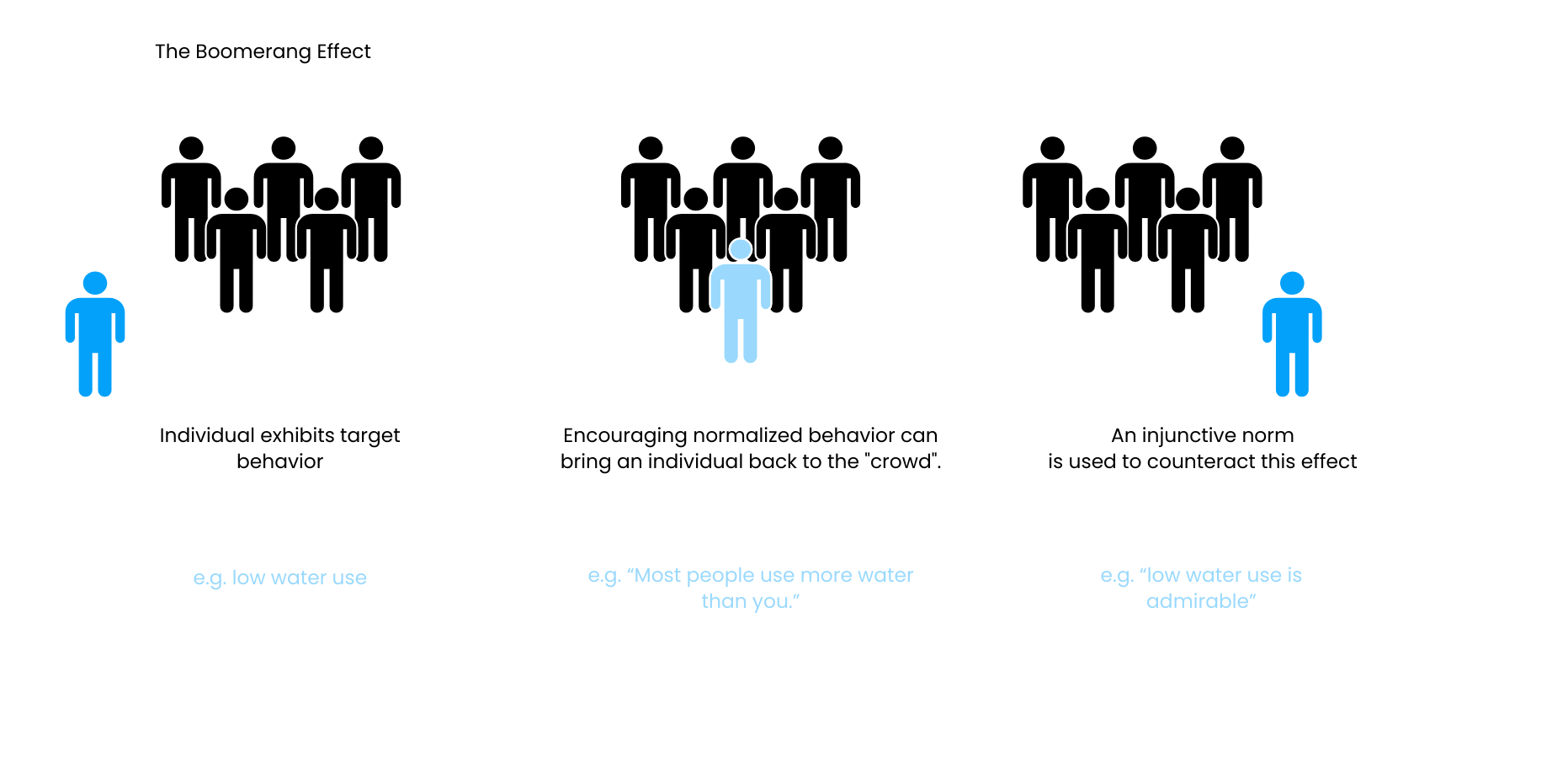

While descriptive norms are important, they can lead to the boomerang effect, which is an accidental increase in socially unacceptable behavior among individuals who initially performed the behavior below the norm.For instance, a social norms campaign to conserve water may cause individuals who consume less water than the norm to start consuming more.

However, injunctive norms can counteract this effect by demonstrating to this group of people that their current behavior is commendable or socially acceptable.

Beyond Social Norms

While social norms are one of the most widely used behavioral tools to reduce resource use, behavioral science offers myriad other insights that can be applied in water efficiency programs. Default options, goal setting, public commitments, and choice overload are four additional principles that—when applied carefully and systematically—hold the potential to produce further gains in water-use efficiency in the residential sector.

/2024%20Resource%20Content%20Thumbnails/Behavioral%20Science.png?width=400&height=166&name=Behavioral%20Science.png)

Water managers can, for example, harness the power of default options by automatically enrolling residents in programs to improve water-use efficiency, and giving them the option to leave the program if they choose. Some research indicates that relatively few people make the effort to opt out. In one instance, just 57 of 20,000 automatically enrolled households chose not to participate in an energy reduction program.

Putting Behavioral Science into Action

The importance of water conservation and efficiency cannot be overstated. Climate change and growing populations threaten to exacerbate global water vulnerabilities. Fortunately, by utilizing behavioral science, we have the opportunity to significantly reduce residential water usage.

By combining information and financial incentives with well-established programs that account for a variety of social and psychological factors, stakeholders can help ensure reliable access to water for everyone.

The need for greater water efficiency is huge. Americans’ water footprint is twice the global average. Climate change and growing populations threaten to exacerbate global water vulnerabilities. By combining information and financial incentives with well-tested programs that take a range of social and psychological factors into account, stakeholders have the potential to make the progress necessary to help provide reliable access to water for all.